First root problem #2: We don’t know how to enable client’s decisions

Run experiments that are cheap to enable decision-making. In this article you learn the necessary iterative pattern.

What did it cost you to run this small experiment of modeling the few sample spaces from last week’s chapter? What did you learn?

We currently follow a waterfall model, starting with a low level of detail and slowly increasing to a very high level. This progress makes sense when drawing plans. However, this waterfall status quo model is no longer suitable for digital workflows.

Many people will now think that tools like Archicad enable them to model already very detailed through preset styles they just have to choose from. Unless you have a very good system, I would not recommend this because navigating all the settings and switching styles takes too much focus (and clicks) away from the conceptual work. This constant shift of attention hinders the work you should do:

Creating good concepts and foundations for decision-making. Keep it very simple, and don’t mix too many different steps.

Run cheap experiments

So, instead of modeling for plans, think about modeling for decision-making. You could argue that plans are needed for decision-making, but I see them as more of a tradition and something professionals learned to work with.

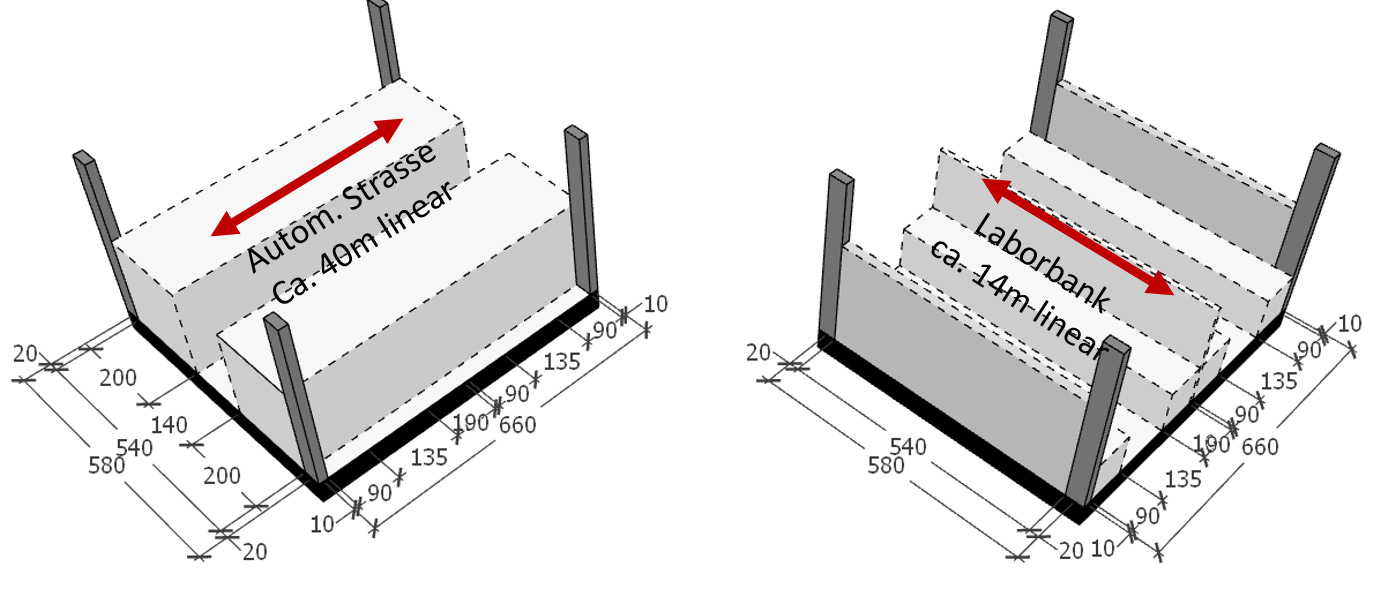

This is an example from a workshop where an interdisciplinary team developed a structural concept for a flexible, future-proof laboratory grid:

In the workshop, we made several sketches and a quick model for documentation. Usually, an architect would do a plan and spend much more time on it! We architects learned to prepare posters, brochures, and renderings and layout them so that they make sense for other architects - but our clients are, most of the time, no architects. Do you remember the story of the pastel-colored plans that were printed in primary colors due to a mistake? Sometimes, our clients or users don’t even know how to read plans. So, plans are a tool, but are they the best for every situation?

I have found an approach from design thinking helpful. We must ask ourselves how to run cheap experiments that enable us to make decisions without investing too many resources. What is the minimum we can model to get a useful model of reality for decision-making?

Often, it will follow this pattern:

A Sketch to clarify the concept (The first experiment).

Use the Sketch to communicate and get others’ relevant input.

Start modeling the minimal necessary geometry and metadata. Remember that it is usually less work to add metadata than to model geometry (The second experiment).

Use this information to optimize the model and run automation to create decision support artifacts, e.g., cost calculation or thermal simulations. (The third experiment).

Repeat and add them together.

So, what’s the difference to a waterfall approach? I think it’s the scale. A waterfall approach to planning works with much larger junks. You start working at the bottom-left side of the screen and finish when you reach the top-right. Compared to this waterfall, I recommend using these steps for isolated problems and when to combine the findings from different experiments in another iteration.

The construction management team of an architectural company I worked for asked me to relocate to Hamburg and support them in a project with another architect. So I sat in his office, trying to bring order into our processes. He was a much better design architect than the office I worked for at this time, but his workflows for detailed design did not exist. But he had a great way of modeling that had a long-lasting impact on me:

Instead of modeling/drawing the walls, he modeled/drew the spaces. To create a good-looking plan, he just drew one big shape in gray and filled the spaces with a very light gray/white. This quick modeling helped him to explore different layout options very quickly. His way of working influenced me in the development of the abstractBIM.

Unfortunately, the common modeling tools like Archicad, Revit, Vectorworks, Plancal Nova, … don’t help here. Out of the box, they focus on modeling to create good-looking plans instead of modeling for decision-making. They focus on modeling walls and slabs instead of the “space”. I like to say:

“Do you want to focus on the walls that separate or the space that connects?”

Interestingly, the McLeamy curve is often used in presentations about BIM to showcase the importance of early decision-making and BIM surprisingly helps her. Unfortunately, using the tools with the “old” mindset does not solve anything. It only makes a lot more work for everybody. Therefore:

Hack the mindset by stopping to complain about clients who don’t make decisions. Instead, empower yourself and consider how to help the client.

Hack your tools by reducing your click rate. Try to develop workflows that enable you to cheaply run experiments tailored toward decision-making with as little effort as possible. Be creative not only in what you do but also in how you do it.

We truly live in exciting times that we can shape how we will work in the future.

Next week, read more about the second root problem.